On Friday I went to an exhibition and film primer, that was 2 years in the making, creatively crafted by the Young Historians Project, and listened to a panel consisting of some of the early pioneers of the Black Liberation Front, a British Black power organization created in 1971. It was fascinating hearing their experiences, and how they laid the foundations for Black Liberation in Britain. At the same time it was eerie listening to their past struggles as they sounded both strangely similar, but also alien to current black struggles in Britain and the diaspora.

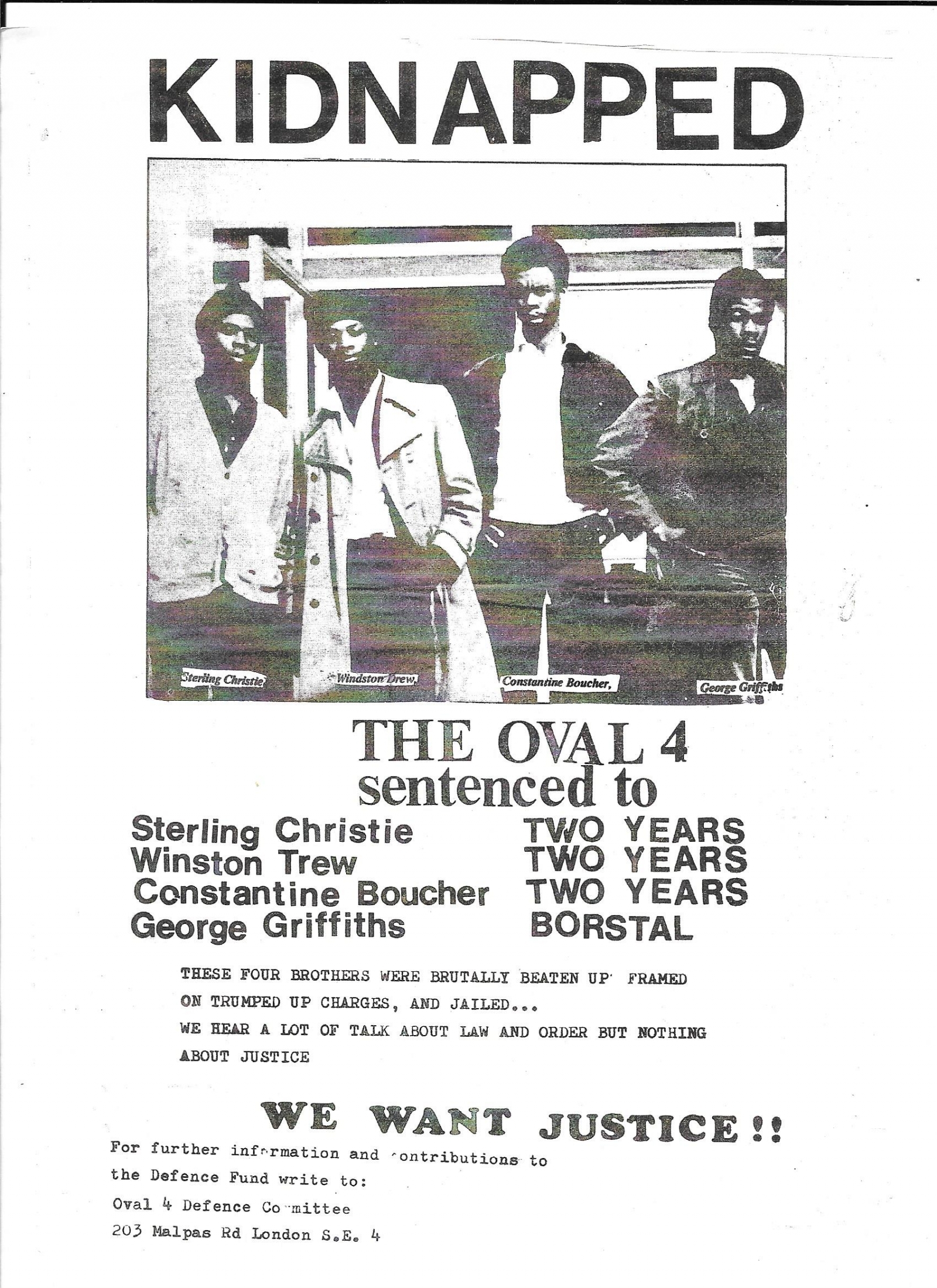

In the context of frequent police brutality, such as the controversial Oval 4 incident that saw four black men assaulted by police over an ‘unproven’ theft and subsequently sent to prison; or the openly fascist and racist political party the National Front, who would terrorize black British people and other ethnic minorities, or the institutional racism in the British education system failing black students at alarming rates- being black in 1970s-1980s Britain was no mean feat.

It’s not to say there isn’t racism in 2017, it’s only just the other day that the FA finally apologised to England striker, and sports lawyer Eni Aluko, admitting ex manager Mark Sampson made remarks which were “discriminatory on the grounds of race” (a fancy way of saying racist), or the race audit that shows that together black and mixed raced people have the highest unemployment rates.

AlthoughI guess the main difference of racial experience that I felt from Friday’s film screening, was that in the face of racist adversity there was a more unified effort to fight against the problems black and ethnic minority people faced, at one point or another the Black Liberation Front, partnered with black progression groups such as the Black Panther Party (both USA and London); the Fasimbas; helped to establish the Committee for Ethiopian and Eritrean Relief; and they had a large international presence in the African diaspora with the help of Zainab Abbas, a true flag bearer for the UK’s Pan-African cause.

It made me realise that we, as a diaspora, are stronger together, and I hope myself and others can implement such a truth on our everyday lives.

The Black Liberation Front:

The Black Liberation Front were a progressive answer to the more overt, brash, violent racism that was rife in 1970s Britian. The Black Liberation Front was founded in 1971 and their activities gradually came to an end in 1993. They took inspiration from the 1960s Civil Rights movement, the USA’s Black Panther Party, anti-colonial and independence struggles in African countries such as South Africa or Ghana, Malcom X, and other socialists organizations around the world.

Friday night made clear to me, that The Black Liberation Front was more than just a black power organization who held politically left meetings. In every sense on the word, the Black Liberation Front made change.

The Black Liberation Front would provide extra-curricular supplementary schools (Saturday Schools), to children of their communities, where they’d be taught Maths, English, and Black culture & History. Having gone to similar Saturday schools when I was younger, at a time when education attainment inequality was no where near as bad for a black child in 1970s Britian, only now can I appreciate the need for such programs, and can only imagine what they did for those children that went back then.

In 1974, the Black Liberation Front made affordable housing for black families and particularly young black homeless people, through creating the Ujima housing association- jointly founded by Tony Soares, one of the original members of the Black Liberation Front. They also had community bookshops and newspapers (Grassroots) to educate and consolidate the black political identity both in Britain and the diaspora, and they would support black prisoners. Unfortunately, the Ujima housing association no longer exists, but maybe if more young black British people of today know about it, we might get inspired to do something similar in the future (*strokes chin*).

Why History Matters?

When asked by Professor Hakim Adi, Historian and founder of the Yong History Project, why recording such history is important. Young black Historian, Kabejja responded by saying:

“because young people nowadays, especially with the visibility of race, and race relations, and police brutality…we don’t have a sort of blue print, we don’t have a reference, and its very important for young people to see something that’s come before them, and the failures are as important as the successes, so that we can look back and see where did it went wrong, and where can we fill in the gaps, and also there’s been a foundation laid, so we don’t have to go down and start from the beginning, we can just build on from what people before us did.”– (Kabbejja Serumaga)

I couldn’t agree anymore with her, and now more than ever I realise how sad it was that I was put off History because of the typical ‘dry’ teacher who was teaching history from a Eurocentric perspective.

Why would you like to be a part of something you can’t see yourself in?

With such questions and statistics such as less than 2% of all history graduates are black, and that amongst black undergraduates, history was the third most unpopular subject–only veterinary science and agriculture were more unpopular, it is clear that their was a need for Professor Hakim Adi to create a platform for young historians from African and Caribbean backgrounds to learn about the history they wanted to, their history.

When Professor Hakim asked Winston Trew, an original member of the Black Liberation Front, why recording such history is important, his response was both inspiring and brought a certain solace to me.

“the history is very important because I joined the black movement as a young man at 19, and I didn’t know what I was getting involved in, but looking back I don’t regret any part of it at all, even being beaten up by the police and going to prison, wrongly, I don’t regret any of it because out of that I became the person who I am today.” -(Winston Trew)

Despite going through a traumatic experience for simply being a black male, Winston Trew, was able to turn his history into a constructive force for the progression of black liberation in Britain, that no doubt influenced other young black men and women going through struggles. It is this acceptance of his history, this reclaiming of your history, whether good or bad that I find inspiring, because regardless of your past- accepting it is the first step in accepting yourself.

The Young Historian Project film was called “We Are Our Own Liberators”, and to me the title speaks volumes, as first and foremost the liberation of the black race needs to come from within, and understanding our past constraints on liberation, as well as past attempts at liberation will help us, the current generation, further progress with this exciting challenge.

Self-determination is key.

Chijioke Anosike TWN Editor

Leave a comment